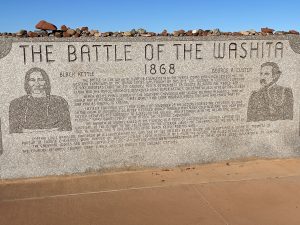

Charles Brill’s account of the November 27, 1868 incident between Black Kettle’s Cheyenne tribe and U.S. 7thCavalry troops led by Lt. Col. George Custer is entitled, Conquest of the Southern Plains: Uncensored Narrative of the Washita and Custer’s Southern Campaign. Brill’s 1938 publication relied on eyewitness accounts from aged Indian survivors of the conflict. Brill personally took Cheyennes Magpie and Little Beaver and Arapaho Left Hand along with government interpreter John Otterby, a.k.a. Lean Elk, to the site of the attack. This article relies on the 2001 republication of Brill’s accounts by the University of Oklahoma Press re-titled Custer, Black Kettle, and the Fight on the Washita.

The fertile Washita River valley area on the western edge of Indian Territory (Oklahoma) had been a common peaceful wintering ground for numerous Indian tribes for countless years before 1868. There was an abundance of water, game, shelter and vegetation. It was also an area set aside for the Indians in several treaties with the United States between Black Kettle’s Cheyenne and other tribes. On the bitterly cold, snow-covered morning of November 27, 1868 the Indians’ only concerns were keeping warm and tending to their horses. Then Custer’s seven hundred mounted soldiers came charging at the sleepy Indians from all sides with rifles blazing and sabers slashing.

Black Kettle was alerted by a woman who had been tending to the horses and first saw the approaching soldiers. When she yelled out “Soldiers, soldiers!”, Black Kettle fired a warning shot with his rifle to awaken the camp. Then Black Kettle drew his wife, Medicine Woman, up behind him on his pony and attempted to flee as he and Medicine Woman shouted warnings to the camp. He and Medicine Woman were then shot and killed. Magpie, one of the eyewitnesses Brill relied upon, heard Black Kettles’ warning shot and exited his lodge just as he heard a trumpet blast from the nearby trees and then saw the mounted soldiers charging into the village from all sides. Magpie was shot in the leg but managed to escape death by entering the freezing water and hiding in the brush along the banks.

As reported by Brill at page 159:

“From every side came the heavy report of carbines. Occasionally an Indian rifle answered. But these were notable for their infrequency. So sudden had been the attack, only a few of the red men had opportunity to arm themselves. Most of those who did so had only bows and arrows. They were powerless to offer serious resistance. Flight was their only objective.

Those villagers whose tepees stood nearest the stream fared better than their friends in the center and on the south side of the camp. First to dash through the icy waters of the Washita and scramble up the opposite bank found themselves running into scouts and sharpshooters who had deployed in the timber there. They also encountered troopers, mounted and dismounted. Seeing escape shut off in that direction, the fugitives accepted the only avenue left open to them, the channel itself. It was misery to wade its ice-fringed waters, but it was either that or bullets.

Women and children, as well as braves, plunged into the stream. Most of them were scantily clad. Many were without moccasins on their feet. Frequently the water reached to the armpits of adults who had to carry the children through these deep pools to prevent their drowning. Desperately they splashed their way beyond the lines of their enemies.”

Sometimes the fog of history eventually is pierced by uncomfortable facts. The Washita massacre was originally reported as a great military victory over savage foes by courageous heroes. Those reports originated from the “heroes”. The facts managed to slowly ooze out over a great deal of time. Those facts established the betrayal of morality and violations of treaties. They do not tell us, “Why?” The reasons may be explained by Pawnee attorney and scholar of law and history Walter R. Echo-Hawk in his book on bad court cases involving Native American treatment by the dominant white culture.

In the Courts of the Conquerors, The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided contemplates the roots of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and its raison d’être, The White Man’s Burden:

“A popular justification for colonialism among the colonizing nations was the white man’s burden. Originally coined by Rudyard Kipling, the term is a euphemism for imperialism based upon the presumed responsibility of white people to exercise hegemony over nonwhite people, to impart Christianity and European values, thereby uplifting the inferior and uncivilized peoples of the world. In this ethnocentric view, non-European cultures are seen as childlike, barbaric, or otherwise inferior and in need of European guidance for their own good. As thus viewed from European eyes, colonization became a noble undertaking done charitably for the benefit of peoples of color.” See p. 16

The concept of exterminating Native American culture as justified because it was replaced with the blessings of Christianity and civilization is hardly a new idea. The Romans by force of arms visited their supposed superior culture on “lesser” peoples as have many dominate societies for thousands of years. The germ of “destroying a culture to save it” is easily discovered by any powerful society that wants to take what some weaker society has. However, that there was ample precedent for the massacre at the Washita does not expiate Custer’s assault and does not obviate the moral imperative to remember it.

Leave a Reply