NO STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS

(Week of October 6, 2005)

On Monday, October 07, 1878,…“[T]hree white girls living very quietly in a retired and lonely part of the city were outraged by negroes.” So said the front page of the The Mt. Vernon Dollar Democrat published October 17, 1878.

The New Harmony Register of Friday, October 11, 1878 reported that Deputy Sheriff Cyrus O. Thomas had been killed Thursday, October 10, 1878 while trying to arrest a Negro who had been indicted by a Posey County Grand Jury for the “outrage”.

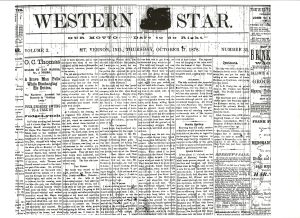

The Western Star, another Posey County weekly newspaper, lead its Thursday, October 17, 1878 front page with the banner headline “Judge Lynch Holds Court.”

Officer Thomas who had been,…“[a] prominent candidate for sheriff”, was described as brave, noble and generous. His death had been avenged by 300 of Posey County’s “best citizens” and the bodies of … “four Negroes were suspended from the large locust tree on the Courthouse Square until after Thomas’s funeral.”

The term Judge Lynch is an oxymoron. To judge is to apply settled law to particular facts using established procedures. To lynch is to kill a human being without any safeguards or due process of law.

William Lynch who lived in Virginia from 1742-1820 acted as a sort of Judge Roy Bean. He set up his own court and made up his own rules. His name became the metonymy (the representative term) for mob rule. For the newspaper to describe such an event as justice dispensed by “Judge Lynch” was a well understood literary device in America when lynchings were more recognizable. It was usually applied to an ultravires (illegal) action which the majority of a community publicly condemned but privately sanctioned. Such was the case in Posey County in October, 1878.

I first learned of the newspaper reports of the death of Captain C.O. Thomas and the circumstances which led up to it and the lynchings which grew out of it from my friend Ilse Horacek on March 14, 1990. Ilse is one of Posey County’s best writers and historians. I had spoken to the Posey County Coterie Literacy Society in the Circuit Court Courtroom about the incident which I had found briefly mentioned in W.P. Leonard’s History and Directory of Posey County. Afterwards, Ilse gave me a copy of one of the articles from 1878. My memory of our conversation from 1990 is that Ilse told me she has a particular interest in C.O. Thomas and the surrounding happenings as her husband’s family is related to Officer Thomas. Some accounts refer to him as O.C. Thomas and others as O.S. Thomas.

The lynchings occurred right outside what was then our brand new courthouse. I am reminded of it whenever I walk across the courthouse campus. And in October each year the events of 1878 feel as though they just occurred.

If you wish to follow along we might relive some of those days. And if you have an old family Bible or diary or letters or other information about the outrage of the white girls or Officer Thomas’s death or the lynchings we could, perhaps, be fairer to the memory of all involved if you would contact me. As we used to say when some other boy would threaten, “I’ll see you after school!”, I am not that hard to find.

A particular artifact that another of my friends, Posey County Historian Glenn Curtis, told me he saw in the barber shop a few years ago was hawked for sale in October, 1878 in The Mt. Vernon Dollar Democrat:

“Mr. Jones, our artist, took photographs of the four

Negroes lynched by the vigilants [sic] last Friday night.

It is an excellent representation of the tragic scene.

Mr. Jones has copies for sale.”

Perhaps one of you may have access to such a photograph or other evidence and together we can investigate what occurred that other October 127 years ago. Let’s talk again next week.

Mt. Vernon’s Belleville, October, 1878

(Week of October 17, 2005)

The “Mt. Vernon Dollar Democrat” described the women alleged to be the victims of the rape of October, 1878, as, “[T]hree white girls living very quietly in a retired and lonely part of the city.” The “girls” lived in an area of Mt. Vernon then known as Belleville.

This area was generally located just north of the Ohio River and south of what was then First Street (now Water Street). This part of Posey County provided much of the flavor for its reputation as a good place for a good time for Ohio River boatmen and others.

The three belles were the named victims of the rapes by Edward Hill, William Chambers, Jim Good, Jeff Hopkins, Ed Warner and “three other Negroes”. The crimes were alleged to have occurred October 07, 1878. These men were indicted by a Posey County Grand Jury on October 08, 1878.

Chambers, Warner, Good and Hopkins were charged with raping Jennie Summers. Ed Warner, Jeff Hopkins and “three other Negroes” were indicted for the rape of Rosa Hughes. Ed Hill and “other unnamed Negroes” were charged with raping Emma Davis.

According to newspaper accounts the men gained entrance to the women’s home by presenting a false note ostensibly from a “white gentleman”. On being admitted the eight proceeded to sexually assault the women while threatening them with a knife and pistol.

Court records from 1878 are still stored in our historic courthouse. The holographic court accounts are devoid of detail but pregnant with character. The penmanship is a work of art and the terminology used often camouflages an ironic sense of humor in our ancestors.

These records are contained in what we judges call Order Books because they are a permanent account of the judge’s court orders.

In the Order Books of 1877 and 1878 are mention of some of the men indicted for the rapes in October, 1878. There were charges for theft and assault. Jim Good had been convicted of a prior sexual assault and William Chambers had been suspected but not convicted of murdering his white prostitute lover, Annie McCool. Jeff Hopkins had been tried and acquitted of an earlier unrelated murder.

And Rosa Hughes, Emma Davis and Jennie Summers appeared regularly in court for prostitution. They were usually fined five dollars and told to go forth and sin no more.

Of course, some of these men who were indicted, four of whom were later lynched, had no record of prior legal difficulties. And, those with court records still deserved due process of law and the presumption of innocence.

And as to the “working girls”, their manner of surviving did not preclude them from the protection of the law nor did it mean they could not be victims of rape.

As with many cases in court today, the fog of the facts requires a reservation of judgment and a diligent inquiry.

With your help we might be able to come to some fair conclusions about the alleged rapes, the death of Deputy Sheriff Oscar C. Thomas and the lynchings on the courthouse campus in October, 1878.

It is, also, possible we might find that our history from October, 1878, has relevant lessons for our lives in Posey County in October, 2005.

Next week we will get into the Coroner’s Inquest of Officer Thomas’s death. Please remember, if you have discovered any information about these Incidents, I am not immune from hearing the entire case.

Eyewitness Testimony from October, 1878

(Week of October 24, 2005)

Should you have wandered across this column on your way to something important the past two weeks you may recall we have been ♫lost in the 70’s♫, the 1870’s.

Our put upon “white girls living very quietly,” our brave Captain Cyrus O. Thomas and our Negro lynch victims are still our concern.

I thought some references to the contemporary (1878) eyewitness accounts might aid those of you who may have information about the events of October, 1878. Perhaps you could search your family memorabilia and share your information.

Ilse Horacek, Jerry King, Linda Young, and Glenn Curtis have generously helped me in researching these incidents. I want to be accurate. You, too, may be able to help shed light on these puzzling moments of Posey County history. If so, please give me a call.

Before we get to the Coroner’s Inquest into the death of Deputy Sheriff Thomas and the lynchings of James Good, Jeff Hopkins, William Chambers and Edward Warner, some general observations about the reliability of eyewitness testimony may be in order.

Elizabeth F. Loftus is one of modern America’s foremost authorities on eyewitness testimony. She is a professor of forensic psychology at the University of California. Loftus has conducted numerous experiments on eyewitness accounts of events. Among her conclusions is that eyewitness testimony is not only subject to factors such as personal prejudice, personal interest, physical and mental incapacity to observe and understand what we think we have seen, fear, excitement, lighting, length of observation, suggestions by others and many other factors, but it often is unshakable even when wrong.

In other words, our eyewitness testimony from October, 1878 should be evaluated carefully just as you would do if you were to decide cases in court today.

Be that as it may, it is all we have to go on as all the circumstantial and physical evidence is now unavailable. So let’s do the best we can with what we can glean from the 127 year old documentation of these first hand observations. And please note that you and I will only have space and time for a cursory exposition of these accounts.

Three eyewitnesses and two medical doctors testified at the Coroner’s Inquest into C.O. Thomas’s death. Daniel Harrison, Sr., the man accused by the Grand Jury of shooting Officer Thomas, gave his account of the incident to a newspaper editor, John C. Leffel, just before Harrison was killed by a lynch mob.

Harrison claimed that he had been shot first that early morning of October 11, 1878. He, also, claimed that on Wednesday, October 09, 1878, his son, Daniel Harrison Jr., had been taken from his home and lynched. Harrison, Sr., told Leffel that on October 10, 1878 three white men came to his home on First Street (Water Street) looking for another of his sons, John. According to Harrison, Sr., Henry Jones, William Combs and George Daniels came into the home at supper time on October 10. Jones put a pistol to Harrison’s head and said “I’m going to kill you tonight.” The three white men then searched the home.

Harrison, Sr. told Leffel that, “I don’t know if my boys ravished the girls. I had nothing to do with it….I am married, have eight children, and I am 51 years old. Take me out and hang me I have no more to say.”

Due to the events of October 09 and 10, Harrison had been sleeping with a loaded shotgun which he fired after he had been shot. He claimed he did not know the men were law officers.

Harrison was shot either through a window to his home (Harrison’s version) or by the law officers after Harrison had shot O.C. Thomas (Officer’s version).

Harrison ran from his home but turned himself in later. He was locked up in the County jail which then was on the east side of the courthouse. He was later assaulted by a lynch mob and cut into pieces which were thrown into the jailhouse privy.

At the Coroner’s Inquest, officers Charles Baker, Edward Hayes, and William Russell testified that they had gone with Deputy Sheriff C.O. Thomas to Daniel Harrison, Sr.’s home on First Street looking to arrest Edward Hill who was one of the men indicted for the alleged assaults on the prostitutes. They walked the few blocks from the jail and got to Harrison’s house about 2:00 a.m.

Baker and Hayes were armed and went to the back of the house. Thomas and Russell had no weapons. They went to the front.

Hayes stated Thomas died instantly which agreed with the medical opinions of Dr.’s Edwin Spencer and Simon Pearse who performed the autopsy on Thomas.

Baker and Russell testified that Thomas lived for about one half hour after the shooting and made statements about who shot him.

Russell testified that immediately after he heard shots fired he went to Thomas who told him: “Bill, I am shot, they have killed me. Don’t let the Negro get away.”

Next week we will review the statements made by the “[T]hree white girls living quietly in a retired and lonely part of the city.” Their establishment was one of several called “Red Ribbon” houses by our German ancestors. It was within three blocks of the courthouse and four blocks of Daniel Harrison’s home.

Their eyewitness accounts of the alleged sexual assaults were, also, published on the front page of John C. Leffel’s “Western Star” newspaper in rather lurid detail.

SHE SAID; HE SAID; THEY’RE DEAD

(Week of October 24, 2005)

I.

SHE SAID

The “three white girls living very quietly in a retired and lonely part of the city” were Jennie Summers, Emma Davis and Rosa Hughes. They lived on Water Street in the “Belleville” section of Mt. Vernon in a “red ribbon” house.

Each woman related her account of the incident occurring Monday, October 7, 1878, to John C. Leffel, editor of the “The Western Star” newspaper. He printed their versions in the October 17 edition of his paper.

Jennie Summers stated that “about 11:00 pm some person stepped to the door and knocked. He said he had a note for us from a white gentleman”. When she opened the door, Jim Good, Jeff Hopkins, Bill Chambers, Ed Warner and Ed Hill rushed through the door with revolvers in their hands. The intruders immediately blew out the lights.

Hopkins and Warner “threw Summers down and ravished her for half an hour.” Then Good and Chambers “went through the same procedure”.

Summers told the newspaper that there were eight Negroes and she was positive of the identity of the four who raped her plus Daniel Harrison (a.k.a. Harris), Jr., who did not accost her. Summers did not recognize the other three.

Emma Davis told Leffel that she was “thrown down and ravished” by Ed Hill who then hid her behind a door and protected her from being attacked by any of the others.

Rosa Hughes stated that Ed Warner was the “first one who ravished me.” After he did this, he “took sick”, went to the door and vomited.

Hughes said that she did not know the identity of the other three Negroes that ravished her, but with revolvers drawn, “they made me get down on all-fours and remain in that position until they each in turn were satisfied”.

On Tuesday, October 8, 1878, a Posey County Grand Jury was convened and indictments for rape were returned against Jim Good, Edward Hill, William Chambers, Jeff Hopkins, Ed Warner and three other “unnamed Negroes”.

When on October 11, Deputy Sheriff Cyrus O. Thomas and three other officers went to the home of Daniel Harrison, Sr. looking to arrest Edward Hill, Thomas was killed by a shotgun blast.

After Harrison, Sr. turned himself in to the authorities, he said he had been shot first and that he did not know the men outside his home were lawmen. Harrison, Sr. claimed his son Dan, Jr. had been taken away and lynched on Wednesday, October 9 by white men with guns. Harrison Sr. was killed by the lynch mob on October 12, 1878. He was 51 years old with a wife and eight children. He owned a farm and two houses in Mt. Vernon.

II.

HE SAID

Editor John Leffel took statements from the lynching victims just before they were hanged from the locust trees on our courthouse campus on October 12, 1878.

Jim Good said, “I’m going to tell the truth before God and Man.” He said he was not guilty and that he could prove where he was the night of October 7.

Good said he did not “ravish the girls” nor did he know who did. He stated he used to lead a gambler’s life but was now a married man with three children and was about 38 years old.

Good was lynched a few minutes after this statement.

Jeff Hopkins related an alibi for the evening of October 7. He claimed he was innocent and could prove it. He said he was married, had five children and was 42 years old. According to the front page account in “the Western Star”, Hopkins, Good, Chambers and Warner were marched out of the jail with their hands tied. “One man walked on the right of each Negro while four men walked on the left holding the ropes in their hands and leading them to the public square.”

When the four men were at the locust trees, “Ropes were quickly thrown over the limbs, and a dozen willing hands had them soon drawn four feet from the ground.”

Leffel did not publish an account of any statement made by Ed Warner. Leffel did witness Warner’s lynching and indicated Warner was the third one hanged. He survived about three minutes.

William Chambers told Leffel he was innocent and related his whereabouts on October 7. But as he was giving his account, “the rope attached to his neck was quickly thrown over a limb, and he was hung before he had time to finish his story.”

III.

THEY’RE DEAD

Officer Cyrus O. Thomas was shot and killed while performing his duty.

Daniel Harrison, Jr. was killed by a mob. He may have been thrown into the furnace of a train’s steam engine.

John Harrison may have been killed and his body stuffed into a hollow tree.

Daniel Harrison, Sr. was shot twice on October 11, 1878, then, while in the Posey County Jail, he was cut into pieces and thrown into the jail’s privy.

Jim Good, William Chambers, Jeff Hopkins and Edward Warner were lynched on our courthouse square.

Edward Hill’s final outcome is unknown, at least to me.

IV.

OBLIVION

Editor John C. Leffel suggested in his newspaper on October 17, 1878, that Posey County should just “let the appropriately dark pall of oblivion cover the whole transaction.” And, for most of the past 127 years that’s what has occurred.

Next week we (or at least I) will examine the legal system’s role in the events of October, 1878.

“THE LAW’S DELAY”

(Week of November 7, 2005)

Hamlet’s uncle murdered Hamlet’s father, married Hamlet’s mother and stole Hamlet’s kingdom. Hamlet was not amused. He, also, was indecisive. Hamlet vacillated between action and relying on the law for justice. He finally chose to take matters into his own hands, but, thereby, doomed himself and others.

Of course, there are reasons for allowing the law to handle society’s problems. Facts can be developed. Charges can be put to the proof. Properly guided juries and judges can make objective decisions. Penalties can be fit to the crimes and the criminal.

Hamlet personally took revenge and bypassed these time-tested safeguards. Disaster resulted to Hamlet, to his family and friends, and to his country of Denmark where there was, indeed, something rotten.

Posey County was subjected to similar choices in October 1878. Unfortunately, we made similar mistakes.

Gentle reader, please note that almost all of the information in these articles about a bygone time was taken from newspaper accounts that were often incomplete and sometimes contradictory. I have had to fill the logical lacunas and factual hiatuses with some surmises. Of course, if you know of better sources, I am open to correction.

When “three white women living in a quiet and lonely part of Mt. Vernon” claimed they had been raped by several African-American men on Monday, October 7, 1878, a Posey County Grand Jury quickly returned indictments against Daniel Harrison, Jr., John Harrison, Jim Good, Jeff Hopkins, Edward Warner, William Chambers, and Edward Hill.

On Tuesday, October 8, 1878, three white vigilantes took Daniel Harrison, Jr., from his father’s home and lynched him or threw him into the furnace of a railroad steam engine. On October 9, 1878, these same men returned to the Harrison home looking for John Harrison. They put a revolver to Daniel Harrison, Sr.’s, head and threatened to kill him. The men did not find John Harrison at the Harrison home, but did later dispose of him by putting his body into a hollow tree just east of Mt. Vernon.

Four white lawmen went to the Harrison home at 2:00 o’clock a.m., on Thursday, October 10, 1878, to arrest Edward Hill, who was rumored to be hiding at the Harrison home. At the time the lawmen arrived, Daniel Harrison, Sr., was home in bed, fully dressed and sleeping with a loaded shotgun due to the earlier instances at his home. During a melee at the home, Deputy Sheriff Cyrus O. Thomas was shot and killed, and Harrison, Sr., was charged with the shooting. Harrison, Sr., who had been shot during the melee, turned himself in that same October 10th morning. He was lodged in the Posey County Jail which was then located on the campus of our present courthouse.

Also, Jeff Hopkins, Jim Good, Edward Warner, and William Chambers had been taken into custody and were incarcerated with Daniel Harrison, Sr., in the Posey County Jail.

On the front page of Posey County’s “Western Star” newspaper edition of October 10, 1878, editors, John C. Leffel and S.D. McReynolds, stated:

“Jeff Hopkins, Jim Good, … and … other Negroes…forced

an entrance into a house of ill-fame on First Street, Monday night,

and raped the inmates there. …Jim Good is not as good as his name,

this being the second time he has been guilty of this crime. …The girls

raped were all white. A little hanging would do Jim Good a great deal

of good.”

Editor Leffel attended the jail break-in and the summary executions that took place two days after his article appeared. Much of the information in this article came from his accounts.

In the early morning hours of October 12, 1878, a mob broke into the jail, cut Daniel Harrison, Sr., into pieces and threw his body into the jail’s privy. Jim Good, Jeff Hopkins, Edward Warner, and William Chambers were dragged out of the jail and hanged from the locust trees ringing the courthouse. The four bodies were left hanging on the square until after the funeral of Cyrus O. Thomas, which took place the afternoon of October 12, 1878.

It was not unusual, especially in the south, for Negro lynch victims to be left hanging for an extended period of time as a “warning” to others who may have, also, “deserved hanging” but who had not been caught.

In 1939, Billie Holiday first performed the song “Strange Fruit”, which was her paean to all those black people who had been lynched.

♫Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scene of magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop. ♫

By leaving the young men hanging on our public square all day, it would have been practically impossible for our law enforcement and judicial communities to be unaware of the lynchings.

However, even though the Posey County Prosecuting Attorney, the Judge and, in fact, most of Southern Indiana knew the men indicted for the rapes of the women and the murder of Officer Thomas had been killed in1878, the legal system kept up a charade that the cases were going to be tried. Every term of court from 1878 to 1881, the cases were called, then “set over to the next term.”

During these three years, no action was taken against the people involved in the deaths of Daniel Harrison, Sr., Daniel Harrison, Jr., John Harrison, Jim Good, Jeff Hopkins, Edward Warner, and William Chambers. In 1881, the Prosecutor, without fanfare, dismissed the indictments against the dead rape defendants. I have not been able to determine the ultimate fate of Edward Hill.

This was not our legal system’s finest hour. Of course, injustice is not the sole province of days gone by. Today, “lynchings” are usually more procedural than literal and can involve letting the guilty go free as well as convicting the innocent. Or they may involve imposing Draconian or effete punishment instead of justice.

I am reminded of what Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas said about his confirmation hearings: “This is simply a high class lynching.” And I recall a recent case in another Southern Indiana county where a young black man was sentenced for non-payment of child support and for assaulting a white police officer who had intervened in a domestic dispute. At the sentencing hearing, the police department filled the courtroom with uniformed officers. Was the judge improperly influenced? Probably not even that judge knows for sure. After twenty-five years of imposing sentences, I can attest that it is not easy to exclude all extraneous factors. Court decisions are already hard enough. Justice is ill served by outside attempts to pressure court proceedings.

Hamlet would have been well advised to let the law, even with its many unsatisfactory outcomes, handle affairs in Denmark.

Usually Shakespeare’s characters personify lessons for all of us.

As for now, the month of October has come and gone again and the spectres that haunt my mind as I walk across the courthouse lawn are less demanding. And though justice may have been delayed one hundred twenty-seven years, perhaps with your help it will not be completely denied.